Interview with Dr. Kristine Hoffmann We asked Dr. Hoffman to share more about herself...

I am a visiting assistant professor at St. Lawrence University, a small liberal arts college in rural New York. I teach undergraduate courses based on herpetology, ecology, statistics, conservation biology, habitat management, domestic dogs, and general biology. I'm best known for my work with a conservation dog, K9 Newt, who is trained to find endangered toads and turtles and for working with the unisexual salamander. My research examines habitat relationships, community ecology, and behavior of amphibians and reptiles.

Where did you grow up and were you raised to be out in nature?

I grew up in Sterling Massachusetts with a vernal pool in my back woods, about 100 feet from our lawn. I was always an animal person and I spent a lot of time catching bugs, watching squirrels, and moving wood frogs off the lawn ahead of the mower. I named all the chipmunks around our house, and pretended I could tell them apart by their locations. My mom says she always knew I would do something with wild animals as a job.

What drove you to pursue nature, and more specifically amphibians and reptiles?

I don’t really like being inside. I need to get some forest time each week for my mental health and to recenter. The woods are like church for me, a sacred space that needs my respect. Plus there’s more bugs in the woods.

Amphibians and reptiles tend to be small and people don’t pay much attention to them. They’re the little guys that everyone overlooks and need someone to speak out for them. When a wave of development passed through my hometown my family got involved in conservation, particularly vernal pool conservation. My dad and I learned how to certify vernal pools and we helped the town’s Conservation Commission determine when a wetland was a vernal pool. We were in the towns’ police log a few times when people didn’t understand what we were up to. I was called something like “Suspicious Lady With Bucket” once.

Is your passion teaching?

I have many passions, but yes, I really love teaching. I get to tell stories about how things work for a living. Working at a college lets me teach adults who usually want to learn about my subjects, while I’m still able to get out into the woods and research or work with different stakeholders. Plus, my students are amazing.

How and why did you become involved in this coloring book collaboration?

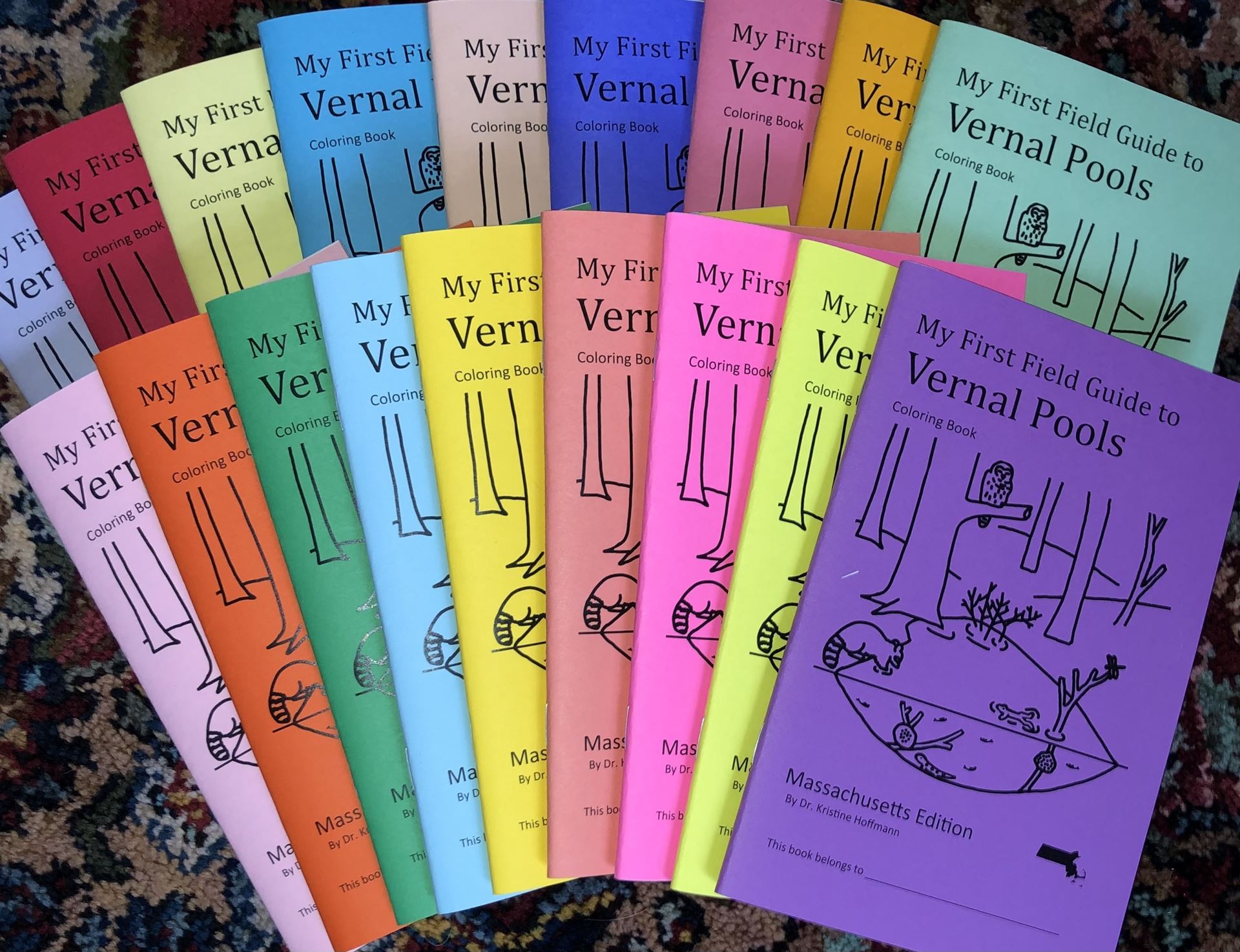

The coloring book was part of a larger outreach project I worked on during my post-doctoral fellowship at UMaine. I had worked with some nature centers and school groups during my doctorate and had spent time thinking about resources that could really help them. Guidebooks tend to be very expensive, and it’s easy to ruin a good book when you’re at a swamp in the rain. A coloring guide would allow each child to have their own cheap and easily replicable guidebook. We also have a sing-a-long song and a web comic series by a student artist on the vernalpools.me website.

What are your 5-10 years goals?

Oh geez, first to get a permanent job, and I might be hired on here at St. Lawrence University - we have an ecologist retiring and I have an application in.

I’ve been working with undergraduate researchers on some behavioral questions about blue-spotted and unisexual salamanders and I hope to learn more about these unusual animals.

I also want to meet with different state biologists and talk about their most urgent information needs so we can try to address some causes of species decline. There’s still no protection for vernal pools in most states, so what information do we need to move forward?

In Rhode Island and New York my students and I have been working with a conservation detection dog, K9 Newt, to find wood turtles. We’re learning about their local distribution, populations, and behavior. There’s a lot of questions we can ask with the dog, but conservation dogs are just now becoming a common method so there’s a lot of questions about how to best use them for reptile and amphibian work too.

What do you absolutely dream of doing?

Honestly, this. I’m already doing my dream job, I just need permanence.

My First Field Guide to Vernal Pools Coloring Book

Acknowledgements

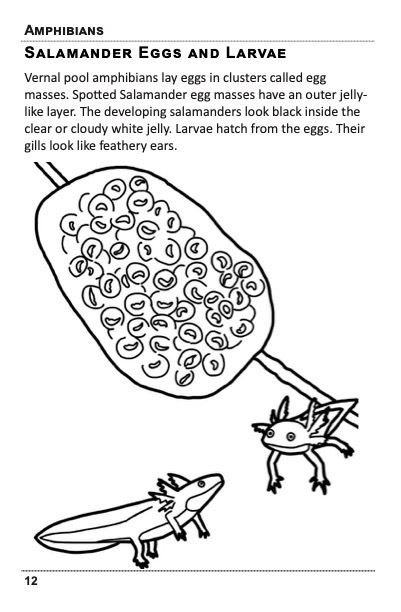

I thank Dr. Aram Calhoun for her enthusiastic support and supervision of this project. Images are based on photographs by Dr. Carly Eakin, Dr. Luke Groff, Dr. Kristine Hoffmann, Lydia Kifner, Dr. Kevin Ryan, Dr. Valorie Titus, and others. Illustrations are by Dr. Kristine Hoffmann. Feedback was provided by Joanne Alex, Dr. Luke Groff, Dr. Malcolm Hunter Jr., Molly Jean Langlais Parker, Celia Johnson, Gudrun Keszoecze, Bram McConnell, and Elizabeth O’Leary. Coloring pages were tested by Alisha Land, Herbie McConnell, Patricia McConnell, Eli Seth Parker, Laurali Langlais Parker, and Piper Stuart Parker. Layout by Rena Carey. This work is copyrighted (2018, 2023) by the University of Maine and Kristine Hoffmann.

Curriculum Vitae

Dr. Kristine Hoffmann earned her BS in Biology from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, her MS in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation from the University of Florida, and her PhD in Wildlife Ecology from the University of Maine in Orono. She was a teaching fellow at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise and a Post-Doctoral Researcher at the University of Maine. She is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at St. Lawrence University in Upstate New York. Research Gate https://www.researchgate.net/profile/ Kristine_Hoffmann

|

My First Guide to Vernal Pools

Coloring Book

is available here on our website at www.capeannvernalpondteam.org

| | | |

Printing Instructions

On home printers, two-sided landscape pdfs often print the back side upside down on the default setting. This is due to the way the paper feeds back into the printer. Many commercial printers don’t have this issue. Do a test print from pages 3-4 since page 2 is blank. If back side is upside down, select: layout, two-sided, short-edge binding and do another test print. That should work.

|

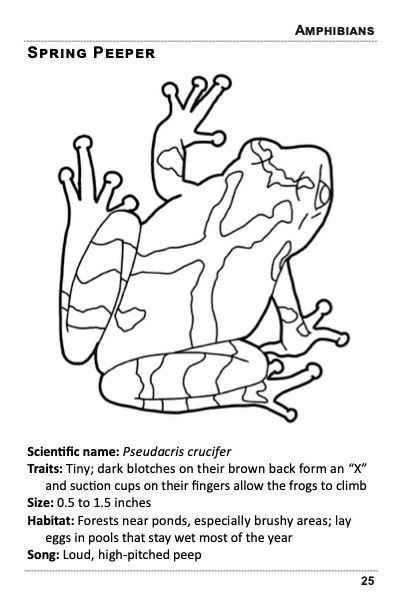

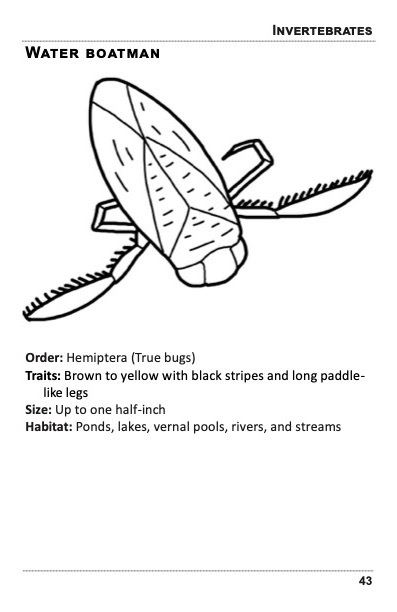

Discovering Vernal PondsVernal ponds are also known as vernal pools and spring pools. They are confined basin depressions with no permanent inlet or outlet; small, shallow, freshwater, temporary fishless wetlands that have a unique ecology. Vernal ponds provide more food for forest wildlife than any other type of wetland. As vital pieces of the larger forest ecosystem, vernal ponds are critical wetland habitat for countless species. Vernal pools host many species of animals, some of which are obligate species -- they require vernal ponds for their survival. The spotted salamander, blue-spotted salamander, Jefferson salamander, marbled salamander, wood frog and fairy shrimp are obligate species in Massachusetts. On Cape Ann we are the home to just three of these obligate species - spotted salamanders, wood frogs and fairy shrimp. In our home area the breeding activity by either the spotted salamander or the wood frog, or the presence of fairy shrimp, is evidence of a vernal pool.

In the spring, wood frogs and salamanders migrate to the ponds to breed. Most of them will return to the same pond every year, and if the pond has been destroyed or disturbed, that specific population will cease to breed. In addition to the species that depend on the specific ponds for survival, there are numerous other invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals that depend on vernal ponds for food.

Because vernal ponds are often small pools of water that dry up in the summer, their significance is sometimes passed over. There are hundreds of vernal ponds on Cape Ann.

Venturing out on your own to find vernal pools is a great way to get outside and make some new discoveries. It's pretty fun and can be done solo or with friends and family. What a rewarding way to have your own adventure from start to finish. By getting into the backwoods and deep into nature, you may decide to help protect these wetlands someday.

Our avid member Adam Bolonsky wrote the article below entitled Oliver to the Rescue for our 2020 Spring Newsletter. Read it and learn more about discovering vernal ponds.

|

OLIVER to the Rescue by Adam Bolonsky

Reprinted from the Cape Ann Vernal Pond Team 2020 Spring Newsletter

When the team first began identifying Cape Ann vernal pools in the early 1990s in Rockport, Gloucester, Manchester, and Essex, we relied almost exclusively on local knowledge. If you were a woodsy, outdoorsy Cape Ann landowner, say, you’d probably noticed there were vernal pools on your property. And if you knew Rick Roth, you’d let him know about them.

If you were a hiker who’d been through Dogtown, Lanesville, Ravenswood Park and other wooded areas, and had an affinity for peering into pools of water, you probably knew what a vernal pool looked like. If you spotted one, you noted its location, contacted a team member, and returned in March or April to measure the pool’s width, length and depth, photograph its relevant egg masses, make note of what kind of vegetation you were in, and did your best to mark the pool’s location on a map. Note: March and April are the only time you can find the egg masses in the pools.

Our efforts were very grassroots. There really wasn’t any other way to get the job done. We hiked around in the woods. We looked around. We made mental or handwritten notes, and simply passed the word.

Our efforts have changed a lot since. Thanks to the state’s comprehensive Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, and geographical information systems (GIS) and the availability of a variety of specialized online maps, we can work a lot faster.

How do we do it now? We download from the state’s helpful OLIVER website, predictions of the exact locations of hundreds of potential vernal pools in any area we choose, from Rockport to Lynnfield. We load the locations into our handheld GPS units, gather up our cameras and our field notebooks, and head out into the woods knowing exactly where to look. We start by looking at ones that lie close to public roads and well-marked hiking areas.

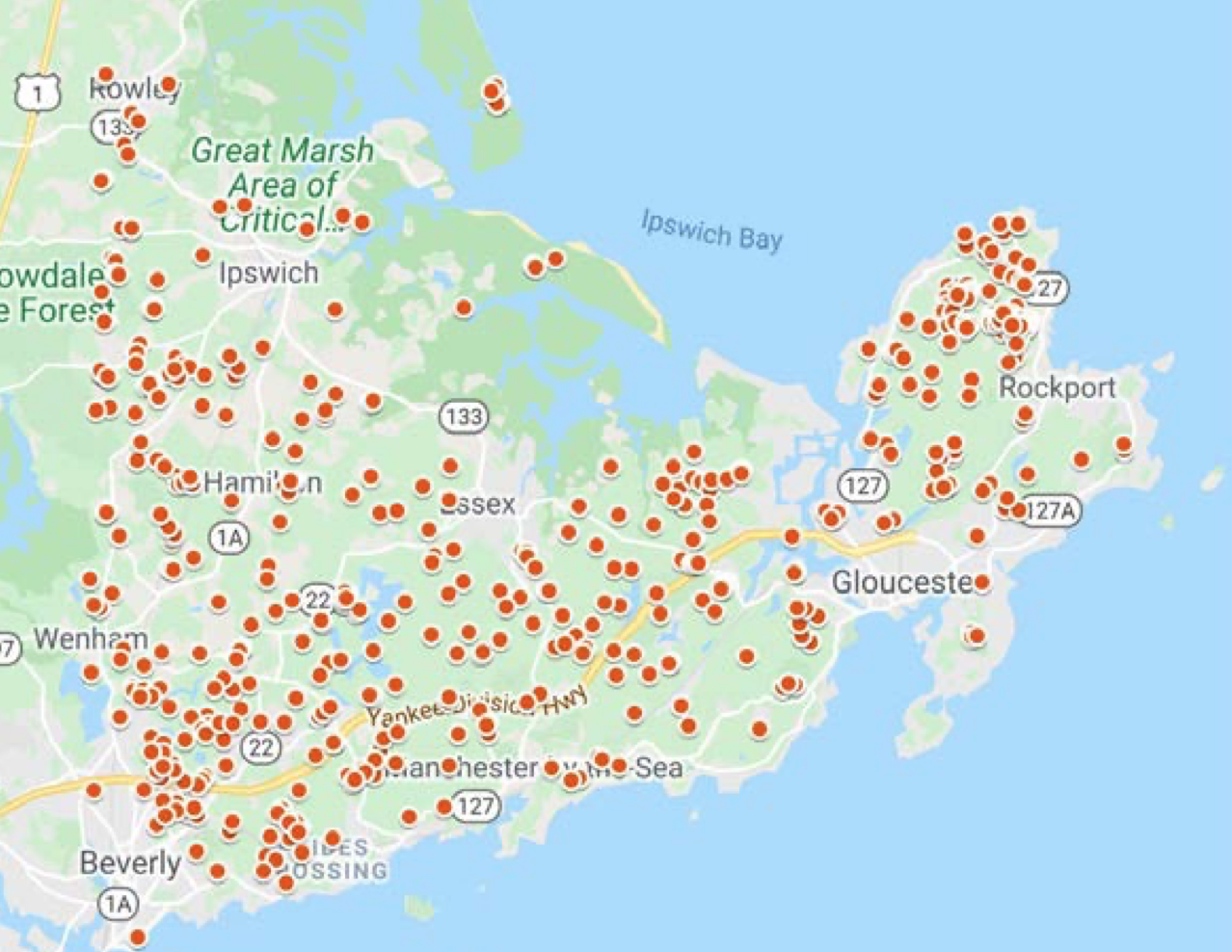

On the left you’ll see the map marking the locations of all the vernal pools we have certified since we began this work almost thirty years ago. In total, we’ve certified over three hundred: each dot on the map represents a pool we took samples from, and reported to the state through its observation portal.

Doesn’t look like there are a lot of dots on that map, does it? Well, as Hamlet said, There’s the rub. Vernal pools on Cape Ann are often so close to one another (sometimes just 10 or 15 feet apart) that a map small enough to fit in the newsletter piles dozens of those dots on top of one another!

The map on the top right shows how many more pools we need to investigate in the coming months. There’s a lot of dots there, aren’t there? To give you an idea of just how much more work we have left to do, the map doesn’t include the potential Cape Ann vernal pools lying west of Route 1A or north of Ipswich. Would you believe me if I told you we still have 466 pools to assess? Well, believe me. We do!

Consider this an invitation to join Nick Taormina, Rick Roth and me in March and April, when we head back into the woods. We’ll show you how to download potential pool locations into our GPS units from OLIVER, how to use the GPS route to find the pool, and finally how to examine, measure, and asses a vernal pool so it meets state re- porting requirements. A team can investigate a dozen pools a day using our new resources.

|

|